Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Sunday, September 15, 2013

But when will Mumbai Eye hosps and large clinics will have neuro-ophthalmologists ....Alok

worst is in Mumbai most do not know if neuro ophthalmologists super super specialty exists. In USA they are everywhere and in India Sankar Netralaya has 5 of them ......Alok

North Shore Eye Care Adds Ophthalmologists Lawrence Buono, MD Christine Speer-Buono, MD To Medical Staff

In their continuing effort to expand their comprehensive eye care services, the doctors and staff of North Shore Eye Care proudly welcome Lawrence M. Buono, M.D., a Fellowship-Trained Neuro Ophthalmologist who trained at the world-renowned Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia, PA and his wife, Christine Speer-Buono, MD a general ophthalmologist.

Southold, Long Island (PRWEB) September 12, 2013

In their continuing effort to expand their comprehensive eye care services, the doctors and staff of North Shore Eye Care proudly welcome Lawrence M. Buono, M.D., a Fellowship-Trained Neuro Ophthalmologist who trained at the world-renowned Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia, PA and his wife, Christine Speer-Buono, MD a general ophthalmologist.

Dr. Buono is a New York native who grew up in the area and enjoys the opportunity to continue practicing on the east end of Long Island. “I am honored by the opportunity to join the medical staff of such a progressive and established eye center as North Shore Eye Care,” said Dr. Buono, who along with his wife have been practicing on the east end of Long Island for nearly nine years. “North Shore Eye Care has a rich tradition of excellence on Long Island and our philosophies on patient care are a perfect fit.”

In addition to Dr. Buono’s extensive experience in treating complex ocular and neuro-ophthalmic conditions, he also has considerable experience with implanting presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses and treating complicated cataract cases. He currently serves on staff at Southampton Hospital, Eastern Long Island Hospital and Peconic Bay Medical Center.

“I love the challenge of treating complex cataract and neuro-ophthalmic conditions,” said Dr. Buono, “but also thoroughly enjoy utilizing all of the breakthroughs in lens implant technology, diagnostics and surgical techniques to help improve our results in standard cataract surgery.”

Dr. Buono completed his medical degree at Thomas Jefferson Medical College. After completion of a medical/surgical internship at the Presbyterian Hospital/ University of Pennsylvania, he returned to New York for his ophthalmology residency at New York Medical College in Valhalla. Upon completion of his residency, he completed a neuro-ophthalmology fellowship at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. Dr. Buono then served as an Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at Duke University in the neuro-ophthalmology and comprehensive ophthalmology divisions and has authored numerous papers in the ophthalmic literature, and has educated medical students, residents, and fellows.

“It is rare to have a physician of Dr. Buono’s training and expertise join our medical staff,” said Jeffrey Martin, MD. “With Dr. Buono’s training and expertise, we feel confident that our level of comprehensive eye care that we now offer out of our six Long Island locations meets or surpasses the services found in the leading eye centers in the world.” Dr. Buono and Dr. Speer-Buono will be practicing in the Southold, Riverhead and Southampton offices of North Shore Eye Care.

Also joining North Shore Eye Care’s medical staff is Dr. Buono’s wife, Christine Speer Buono, MD, FACS. Dr. Speer Buono graduated from Vanderbilt University with a degree in Chemistry and Spanish, then returned to her home state of Arkansas to receive her medical degree and graduate first in her class from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. She completed an internship at Georgetown Hospital/ INOVA Fairfax Hospital and then residency at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, PA. After her residency completion, Dr. Buono became an Assistant Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology at the Duke Eye Center where she practiced comprehensive ophthalmology including cataract surgery.

She also educated medical students and residents through lectures, clinics, and surgical staffing. Since that time, Dr. Buono has enjoyed being a part of this outstanding practice on the East End. Her interests include cataract surgery, laser surgery for glaucoma and after cataract surgery, dry eye, glaucoma, herpetic eye disease, and other anterior segment disorders. She enjoys caring for and being a part of our community. She is on staff at Southampton Hospital and the Suffolk Surgery Center.

“Ophthalmology provides me ample opportunities to enrich the lives of my patients,” said Dr. Buono, “and I consider it an honor to help make a measurable difference in their lives every day.”

The entire medical staff at North Shore Eye Care is proud to have the husband and wife ophthalmic team on staff. “Dr. Buono and his wife have brought a wealth of knowledge in several areas of ophthalmic care to our practice and have been excellent additions to our growing team of surgeons,” said Dr. Martin.

The entire medical staff at North Shore Eye Care is proud to have the husband and wife ophthalmic team on staff. “Dr. Buono and his wife have brought a wealth of knowledge in several areas of ophthalmic care to our practice and have been excellent additions to our growing team of surgeons,” said Dr. Martin.

North Shore Eye Care is Long Island’s most established full-service comprehensive eye care provider. This year they are celebrating 50 years of eye care excellence since Dr. Sidney Martin founded the practice in 1962. North Shore Eye Care is also the official Eye Care Provider for the New York Islanders and the official LASIK Providers of the New York Mets. Many of their doctors have been voted ‘TOP DOCTORS’ in the New York Metro Area by Castle Connolly and North Shore Eye Care has earned ‘Best Of Long Island’ honors for the past few years.

North Shore Eye Care maintains offices in Smithtown, Riverhead, Holbrook, Deer Park, Southampton and Southold. They specialize in cataract care, LASIK laser vision correction, glaucoma management, diabetic eye disease, oculoplastics, neuro-ophthalmology, and retinal care. For more information about North Shore Eye Care, please contact Jacqueline Hernandez at 631-265-8780.

Contact Jacqueline Hernandez

Office: 631-265-8780

Email: Jacqueline(at)nsEYE(dot)com

Office: 631-265-8780

Email: Jacqueline(at)nsEYE(dot)com

From: Google Alerts <googlealerts-noreply@google.com>

Date: Fri, Sep 13, 2013 at 4:26 PM

Subject: Google Alert - neuro-ophthalmologists

To: atholiya@gmail.com

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/9/prweb11114115.htm

Date: Fri, Sep 13, 2013 at 4:26 PM

Subject: Google Alert - neuro-ophthalmologists

To: atholiya@gmail.com

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/9/prweb11114115.htm

| News | 1 new result for neuro-ophthalmologists |

| North Shore Eye Care Adds Ophthalmologists Lawrence Buono, MD ...PR Web (press release)

Upon completion of his residency, he completed a neuro-ophthalmology fellowship at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. Dr. Buono then served as an ...

See all stories on this topic » | ||

Thursday, September 5, 2013

I am diagonised with Right Mastoiditis and Chronic Right Maxillary sinus.....Shows MRI @ Ambani : on 4ht Sep 2013

Do not know whether to go to ENT or Neurologist or Onco or Interventionist or ???? Pl. talk to ur friend doctor if any and advise......Alok

Why I went for MRI: I hv a Right optic nerve and chiasm atrophy means right eye optic nuritis. Besides I hv constant headache on right side.

Mastoiditis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

| Mastoiditis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

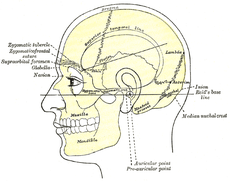

Side view of head, showing surface relations of bones. (Mastoid process labeled near center.)

|

|

| ICD-10 | H70 |

| ICD-9 | 383.0-383.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 22479 |

| MedlinePlus | 001034 |

| eMedicine | emerg/306 ped/1379 |

| MeSH | D008417 |

Contents

Features

Some common symptoms and signs of mastoiditis include pain, tenderness, and swelling in the mastoid region. There may be ear pain (otalgia), and the ear or mastoid region may be red (erythematous). Fever or headaches may also be present. Infants usually show nonspecific symptoms, including anorexia, diarrhea, or irritability. Drainage from the ear occurs in more serious cases, often manifest as brown discharge on the pillowcase upon waking.[4][5]Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mastoiditis is clinical—based on the medical history and physical examination. Imaging studies provide additional information; The standard method of diagnosis is via MRI scan although a CT scan is a common alternative as it gives a clearer and more useful image to see how close the damage may have gotten to the brain and facial nerves. Planar (2-D) X-rays are not as useful. If there is drainage, it is often sent for culture, although this will often be negative if the patient has begun taking antibiotics. Exploratory surgery is often used as a last resort method of diagnosis to see the mastoid and surrounding areas.[2][6]Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of mastoiditis is straightforward: bacteria spread from the middle ear to the mastoid air cells, where the inflammation causes damage to the bony structures. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common organisms recovered in acute mastoiditis. Organisms that are rarely found are Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative aerobic bacilli, and anaerobic bacteria.[7] P. aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae, S. aureus and anaerobic bacteria (Prevotella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, and Peptostreptococcus spp. ) are the most common isolates in chronic mastoiditis.[8] Rarely, Mycobacterium species can also cause the infection. Some mastoiditis is caused by cholesteatoma, which is a sac of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the middle ear that usually results from repeated middle-ear infections. If left untreated, the cholesteatoma can erode into the mastoid process, producing mastoiditis, as well as other complications.[4]Prevention and treatment

In general, mastoiditis is rather simple to prevent. If the patient with an ear infection seeks treatment promptly and receives complete treatment, the antibiotics will usually cure the infection and prevent its spread. For this reason, mastoiditis is rare in developed countries. However, the rise of "superbugs" that are resistant to conventional antibiotics increases the risk that ear infections will worsen into mastoiditis. Most ear infections occur in infants as the eustachian tubes are not fully developed and don't drain readily.In the United States the primary treatment for mastoiditis is administration of intravenous antibiotics. Initially, broad-spectrum antibiotics are given, such as ceftriaxone. As culture results become available, treatment can be switched to more specific antibiotics directed at the eradication of the recovered aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.[8] Long-term antibiotics may be necessary to completely eradicate the infection.[4] If the condition does not quickly improve with antibiotics, surgical procedures may be performed (while continuing the medication). The most common procedure is a myringotomy, a small incision in the tympanic membrane (eardrum), or the insertion of a tympanostomy tube into the eardrum.[6] These serve to drain the pus from the middle ear, helping to treat the infection. The tube is extruded spontaneously after a few weeks to months, and the incision heals naturally. If there are complications, or the mastoiditis does not respond to the above treatments, it may be necessary to perform a mastoidectomy: a procedure in which a portion of the bone is removed and the infection drained.[4]

Prognosis

With prompt treatment, it is possible to cure mastoiditis. Seeking medical care early is important. However, it is difficult for antibiotics to penetrate to the interior of the mastoid process and so it may not be easy to cure the infection; it also may recur. Mastoiditis has many possible complications, all connected to the infection spreading to surrounding structures. Hearing loss is likely, or inflammation of the labyrinth of the inner ear (labyrinthitis) may occur, producing vertigo and an ear ringing may develop along with the hearing loss, making it more difficult to communicate. The infection may also spread to the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), causing facial-nerve palsy, producing weakness or paralysis of some muscles of facial expression, on the same side of the face. Other complications include Bezold's abscess, an abscess (a collection of pus surrounded by inflamed tissue) behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the neck, or a subperiosteal abscess, between the periosteum and mastoid bone ( resulting in the typical appearance of a protruding ear). Serious complications result if the infection spreads to the brain. These include meningitis (inflammation of the protective membranes surrounding the brain), epidural abscess (abscess between the skull and outer membrane of the brain), dural venous thrombophlebitis (inflammation of the venous structures of the brain), or brain abscess.[2][4]Epidemiology

In the United States and other developed countries, the incidence of mastoiditis is quite low, around 0.004%, although it is higher in developing countries. The condition most commonly affects children aged from two to thirteen months, when ear infections most commonly occur. Males and females are equally affected.[3]References

- ^ Diseases of ear nose & throat by PL dhingra & shruti dhingra. published by elsevier

- ^ a b c d "Mastoiditis". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 30, 2003.

- ^ a b "Ear Infections – Treatment". webmd.com. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Young, Tesfa. "Mastoiditis". eMedicine. Retrieved June 10, 2005.

- ^ "What to Do About Ear infections". webmd.com. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ a b Bakhos D, Trijolet JP, Morinière S, Pondaven S, Al Zahrani M, Lescanne E (2011 Apr). "Conservative management of acute mastoiditis in children". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 137(4): 346–50.

- ^ Nussinovitch M, Yoeli R, Elishkevitz K, Varsano I (2004). "Acute mastoiditis in children: epidemiologic, clinical, microbiologic, and therapeutic aspects over past years". Clin Pediatr (Phila) 43: 261–7.

- ^ a b Brook I (2005). "The role of anaerobic bacteria in acute and chronic mastoiditis". Anaerobe 11: 252–7.

Further reading

- Durand, Marlene & Joseph, Michael. (2001). Infections of the Upper Respiratory Tract. In Eugene Braunwald, Anthony S. Fauci, Dennis L. Kasper, Stephen L. Hauser, Dan L. Longo, & J. Larry Jameson (Eds.), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (15th Edition), p. 191. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Cummings CW, Flint PW, Haughey BH, et al. Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo; Mosby; 2005:3019–3020.

- Mastoiditis E Medicine

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Maxillary sinus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

| Maxillary sinus | |

|---|---|

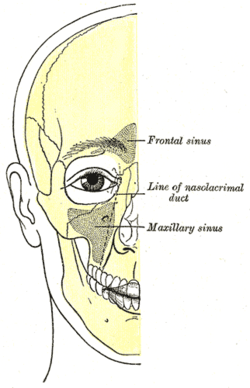

|

|

| Outline of bones of face, showing position of air sinuses. | |

| Latin | sinus maxilliaris |

| Gray's | subject #223 999 |

| Artery | infraorbital artery, posterior superior alveolar artery |

| Nerve | posterior superior alveolar nerve, middle superior alveolar nerve, anterior superior alveolar nerve, and infraorbital nerve |

| MeSH | Maxillary+Sinus |

Contents

Development

It is present at birth as rudimentary air cells, and develops throughout childhood.Discovery

The maxillary sinus was first discovered and illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, but the earliest attribution of significance was given to Nathaniel Highmore, the British surgeon and anatomist who described it in detail in his 1651 treatise.[2]Structure

Found in the body of the maxilla, this sinus has three recesses: an alveolar recess pointed inferiorly, bounded by the alveolar process of the maxilla; a zygomatic recess pointed laterally, bounded by the zygomatic bone; and an infraorbital recess pointed superiorly, bounded by the inferior orbital surface of the maxilla. The medial wall is composed primarily of cartilage. The ostia for drainage are located high on the medial wall and open into the semilunar hiatus of the lateral nasal cavity; because of the position of the ostia, gravity cannot drain the maxillary sinus contents when the head is erect (see pathology). The ostium of the maxillary sinus is high up on the medial wall and on average is 2.4 mm in diameter; with a mean volume of about 10 ml.[3][1] Stand near the person during an extraoral examination to visually inspect and bilaterally palpate the maxillary sinuses.[4]The sinus is lined with mucoperiosteum, with cilia that beat toward the ostia. This membrane is also referred to as the "Schneiderian Membrane", which is histologically a bilaminar membrane with ciliated columnar epithelial cells on the internal (or cavernous) side and periosteum on the osseous side. The size of the sinuses varies in different skulls, and even on the two sides of the same skull.[3]

The infraorbital canal usually projects into the cavity as a well-marked ridge extending from the roof to the anterior wall; additional ridges are sometimes seen in the posterior wall of the cavity and are caused by the alveolar canals.

The mucous membranes receive their postganglionic parasympathetic nerve innervation for mucous secretion originating from the greater petrosal nerve (a branch of the facial nerve). The superior alveolar (anterior, middle, and posterior) nerves, branches of the maxillary nerve provide sensory innervation.

Nasal wall/base

Its nasal wall, or base, presents, in the disarticulated bone, a large, irregular aperture, communicating with the nasal cavity.In the articulated skull this aperture is much reduced in size by the following bones:

- the uncinate process of the ethmoid above,

- the ethmoidal process of the inferior nasal concha below,

- the vertical part of the palatine behind,

- and a small part of the lacrimal above and in front.

Posterior wall

On the posterior wall are the alveolar canals, transmitting the posterior superior alveolar vessels and nerves to the molar teeth.Floor

The maxillary sinus can normally be seen above the level of the premolar and molar teeth in the upper jaw. This dental x-ray film shows how, in the absence of the second premolar and first molar, the sinus became pneumatized and expanded towards the crest of the alveolar process (location at which the bone meets the gum tissue).

Projecting into the floor of the antrum are several conical processes, corresponding to the roots of the first and second maxillary molar teeth; in some cases the floor can be perforated by the apices of the teeth.

Pathology

Maxillary sinusitis

Maxillary sinusitis is inflammation of the maxillary sinuses. The symptoms of sinusitis are headache, usually near the involved sinus, and foul-smelling nasal or pharyngeal discharge, possibly with some systemic signs of infection such as fever and weakness. The skin over the involved sinus can be tender, hot, and even reddened due to the inflammatory process in the area. On radiographs, there is opacification (or cloudiness) of the usually translucent sinus due to retained mucus.[4]Maxillary sinusitis is common due to the close anatomic relation of the frontal sinus, anterior ethmoidal sinus and the maxillary teeth, allowing for easy spread of infection. Differential diagnosis of dental problems needs to be done due to the close proximity to the teeth since the pain from sinusitis can seem to be dentally related.[1] Furthermore, the drainage orifice lies near the roof of the sinus, and so the maxillary sinus does not drain well, and infection develops more easily. The maxillary sinus may drain into the mouth via an abnormal opening, an oroantral fistula, a particular risk after tooth extraction.

Sinusitis treatment

Traditionally the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis is usually prescription of a broad-spectrum cephalosporin antibiotic resistant to beta-lactamase, administered for 10 days. Recent studies have found that the cause of chronic sinus infections lies in the nasal mucus, not in the nasal and sinus tissue targeted by standard treatment. This suggests a beneficial effect in treatments that target primarily the underlying and presumably damage-inflicting nasal and sinus membrane inflammation, instead of the secondary bacterial infection that has been the primary target of past treatments for the disease. Also, surgical procedures with chronic sinus infections are now changing with the direct removal of the mucus, which is loaded with toxins from the inflammatory cells, rather than the inflamed tissue during surgery. Leaving the mucus behind might predispose early recurrence of the chronic sinus infection. If any surgery is performed, it is to enlarge the ostia in the lateral walls of the nasal cavity, creating adequate drainage.[4]Cancer

Carcinoma of the maxillary sinus may invade the palate and cause dental pain. It may also block the nasolacrimal duct. Spread of the tumor into the orbit causes proptosis.[1]Age

With age, the enlarging maxillary sinus may even begin to surround the roots of the maxillary posterior teeth and extend its margins into the body of the zygomatic bone. If the maxillary posterior teeth are lost, the maxillary sinus may expand even more, thinning the bony floor of the alveolar process so that only a thin shell of bone is present.[4]Additional Images

Mastoiditis

Mastoiditis is an infection of the mastoid bone of the skull. The mastoid is located just behind the ear.

Causes

Mastoiditis is usually caused by a middle ear infection (acute otitis media). The infection may spread from the ear to the mastoid bone of the skull. The mastoid bone fills with infected materials and its honeycomb-like structure may deteriorate.Mastoiditis usually affects children. Before antibiotics, mastoiditis was one of the leading causes of death in children. Now it is a relatively uncommon and much less dangerous condition.

Symptoms

- Drainage from the ear

- Ear pain or discomfort

- Fever, may be high or suddenly increase

- Headache

- Hearing loss

- Redness of the ear or behind the ear

- Swelling behind ear, may cause ear to stick out

Exams and Tests

An examination of the head may reveal signs of mastoiditis. The following tests may show an abnormality of the mastoid bone:- CTscan of the ear

- Head CT scan

Treatment

Mastoiditis may be difficult to treat because medications may not reach deep enough into the mastoid bone. It may require repeated or long-term treatment. The infection is treated with antibiotics by injection, then antibiotics by mouth.Surgery to remove part of the bone and drain the mastoid (mastoidectomy) may be needed if antibiotic therapy is not successful. Surgery to drain the middle ear through the eardrum (myringotomy) may be needed to treat the middle ear infection.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Mastoiditis is curable with treatment. However, it may be hard to treat and may come back.Possible Complications

- Destruction of the mastoid bone

- Dizziness or vertigo

- Epidural abscess

- Facial paralysis

- Meningitis

- Partial or complete hearing loss

- Spread of infection to the brain or throughout the body

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your health care provider if you have symptoms of mastoiditis.Call for an appointment with your health care provider if:

- You have an ear infection that does not respond to treatment or is followed by new symptoms

- Your symptoms do not respond to treatment

Prevention

Promptly and completely treating ear infections reduces the risk of mastoiditis.References

Chole RA, Sudhoff HH. Chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, and petrositis. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund LJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:chap 139.Klein JO. Otitis externa, otitis media, and mastoiditis. In:Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009:chap57.

O’Handley JG, Tobin EJ, Shah AR. Otorhinolaryngology. In: Rakel RE, ed. Textbook of Family Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 19.

Update Date: 8/30/2012

Updated by: Linda J. Vorvick, MD, Medical Director and Director of Didactic Curriculum, MEDEX Northwest Division of Physician Assistant Studies, Department of Family Medicine, UW Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington. Seth Schwartz, MD, MPH, Otolaryngologist, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, Washington. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)